China’s Post-Pandemic Euphoria Didn’t Last – Moody’s Analytics

Katrina Ell, director of economic research, Moody’s Analytics and Harry Murphy Cruise, economist and assistant director, Moody’s Analytics, provide a commentary on the situation facing China’s economy.

2023 was supposed to be the year that China’s economy roared back to life as COVID-19 lockdowns moved into the rear-view mirror. But it hasn’t panned out that way. The euphoria that followed China’s reopening early 2023 quickly faded. China’s economic recovery has disappointed all expectations. There are numerous emphatic weak points including household spending, the property market, private investment and high youth unemployment.

China’s economy is forecast to grow 5.1% in 2023, after the weak 2.9% in 2022. But that won’t happen easily; ongoing and more generous fiscal and monetary stimulus is needed and expected to help domestic demand find a floor. Support from stimulus is more important than ever as exports are struggling with the weakened global economy.

Households and businesses keeping purse strings tight

Consumers remain skeptical about the recovery, and this is keeping a lid on spending. Contributing to the weakness is high youth unemployment, which hit a record high in June, with more than one in five young people unable to find work. This group have a high marginal propensity to spend, but without secure unemployment are unable to freely open their wallets.

Private enterprise is also reluctant to spend and invest. Firms took a battering through the pandemic, with repeated lockdowns and sudden policy shifts inhibiting their ability to operate.

The property market

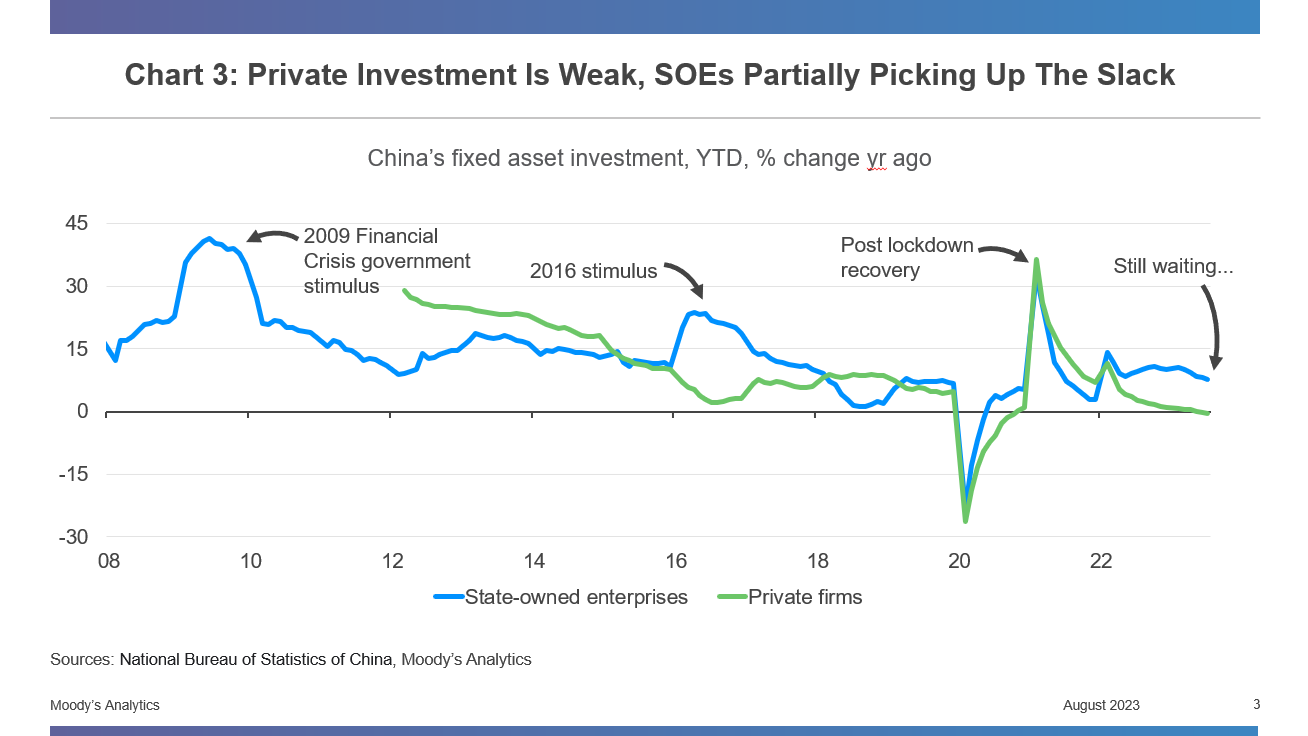

The property market is both a source of weakness and cause for ongoing concern. Around 25% of China’s economy is tied to real estate. With dwelling investment persistently retreating, much of the economy is unable to fire (see Chart 1). This is a large part of why private fixed asset investment has fallen across the first seven months of the year and why industrial production is undershooting expectations.

Policymakers are deliberately avoiding injecting generous stimulus in the property market for concern about reinflating a bubble and pushing leverage higher. But this is having widespread negative spillovers, including for local governments. For instance, local governments have historically relied upon income from land sales and the subsequent constrained cash flow is hurting their ability to repay loans and this is coming at a time when local government bonds have a higher than usual proportion due for repayment.

Shadow banking and the broader financial system have also been impacted by the sustained slump in the property market. But it is unclear the level of contagion and stress this will deliver. One possibility is that heightened and sustained liquidity issues in shadow financing could see small-to-medium size enterprises, which rely on this financing channel, come under further strain. Large property developers are already feeling the pinch, with some unable to meet debt obligations.

Chart 1

The weak export channel

While domestic demand is subdued, external demand is not much better. Exports are weak as households around the world are pulling back on spending and business investment is cooling amid the high interest rate environment (see Chart 2). Borrowing costs are expected to remain restrictive for at least another year, offering little relief for China’s struggling exporters. The broader shift of global spending back towards services following the surge in goods purchases through 2020 and 2021 has brought extra pain to China’s export-oriented firms.

Chart 2

Further stimulus incoming

To try and arrest China’s floundering recovery, modest stimulus has been rolled out including support for domestic tourism, electric vehicle sales and pledges to improve the foreign investment environment. Heavily indebted local governments have also been given some relief including via loan extensions. The People’s Bank of China has also cut a series of key lending rates to help encourage spending and private investment. Still, these measures are unlikely to turn around the recovery in their current form. In fact, the potency of existing stimulus has been reduced by sustained weakness in household and business sentiment.

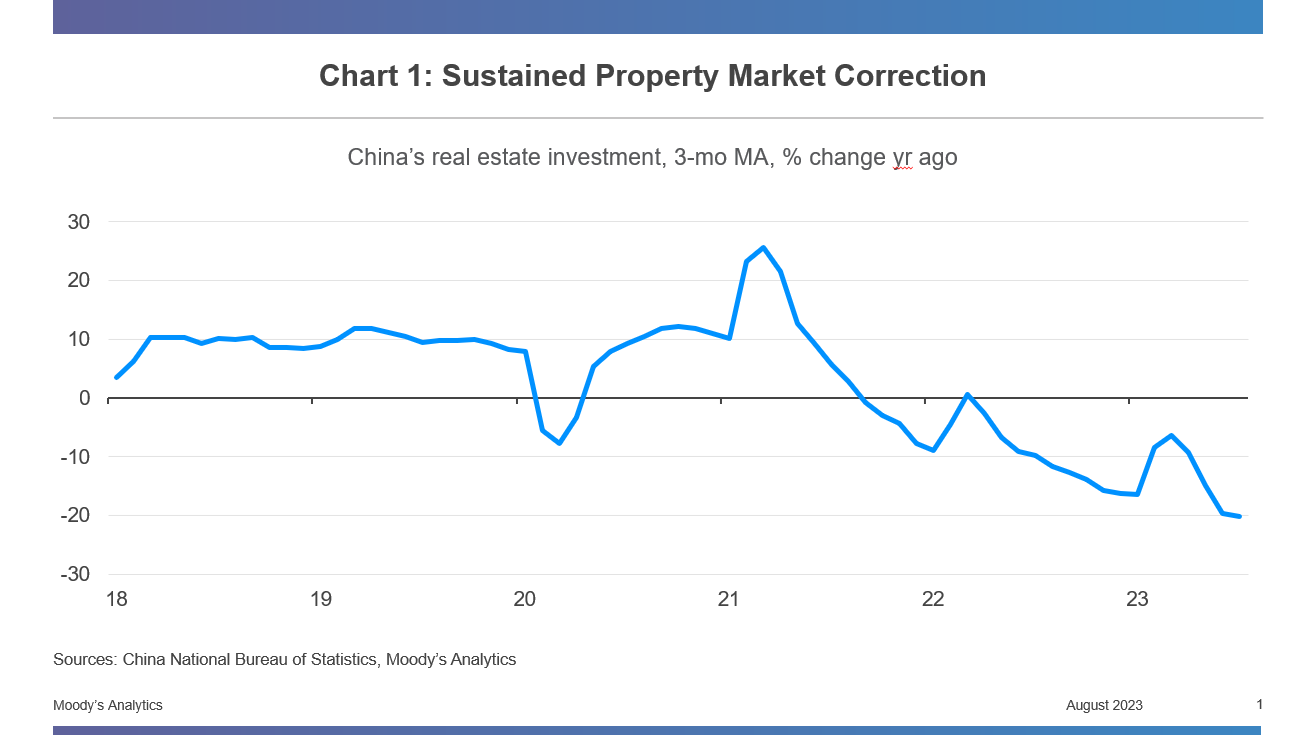

To help counter that, more monetary and fiscal stimulus is expected. But don’t expect reinvigorating stimulus harking back to 2009 when the government’s primary focus was on lifting growth and did so via a tsunami of infrastructure spending (see Chart 3). In 2023, Beijing remains acutely aware that debt-fueled spending isn’t a sustainable or wise method. Instead, another cut to policy rates is expected in the September quarter. Further targeted fiscal support is also on the cards, focusing on households with benefits to be realised through the back end of the year.

It should get better

A lift in consumer spending will help the country’s struggling retailers and manufacturers. Many have been taking a wait-and-see approach, holding off ramping up production and investment until consumers show a willingness to shake off their jitters.

State-owned enterprises are partially picking up the slack, but private firms tend to be more productive and create more jobs than their state-owned counterparts.